From Morocco to Afghanistan, New Book edited by Dr. Michael Kidd gives Insights into Family Medicine in the Countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region

From Afghanistan and Syria to Morocco and Sudan, the countries within North Africa, the Middle East and Western Asia are socio-economically and culturally diverse and face unique challenges, including how they provide health care for their citizens.

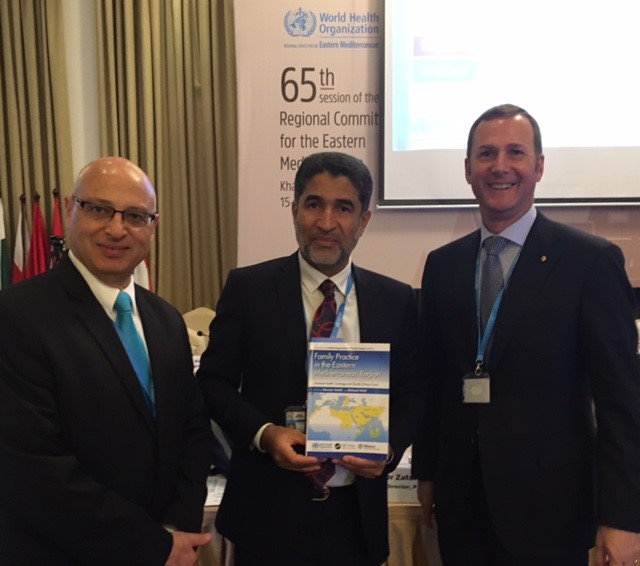

Chair of the University of Toronto Department of Family and Community Medicine, Dr. Michael Kidd, is one of the editors of a newly released book that is the first of its kind to examine family practice and community-based health care in countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region. The book, Family Practice in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: Universal Health Coverage and Quality Primary Care, is a joint publication from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA) and provides an in-depth analysis on how countries in the region are implementing models of family practice.

We spoke to Dr. Kidd about the book and the lessons it can provide for health care providers, policy makers, students and researchers – and the public at large - from within and outside the region.

How would you describe the book and the region it covers?

The book is about the development of family practice in the countries of North Africa and the Middle East, which make up the Eastern Mediterranean Region of the WHO. The region goes from Morocco in the west to Afghanistan in the east and all across North Africa and the Middle East. It’s a very large region of the world and includes wealthy countries, like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, middle-income countries, like Egypt and Jordan, and low-income countries, such as Somalia and Djibouti. It also includes a number of countries which are in crisis and facing unique challenges it comes to delivering health services, like Afghanistan, Libya, Iraq and Syria.

The idea for the book came out of discussions with WHO representatives from the region about how family medicine is taking off in some countries and not others. We structured the book to allow for comparisons between the countries so readers from both within and outside the region can learn about successes and challenges. We also describe a number of overarching issues within several countries, including the health and education of the health workforce, the barriers to implementing a family practice model, quality improvement, research and evaluation in family practice and more.

What role can family medicine play in addressing some of the challenges of the region?

We know that those countries that invest in strong primary care and community-based health care - and that includes family medicine - tend to be countries that have lower health care costs, more equitable access to health care services, and are more likely to address the needs of their vulnerable and marginalized populations.

Countries that have a strong family medicine presence, like Canada, also tend to have fewer people attending emergency departments and less use of expensive hospital services and other services like laboratory and radiology services. That’s one of the reasons the 22 health ministers from each of the countries in the Eastern Mediterranean Region came together with the WHO and committed to implementing a family practice model: they see it as being a way to deliver health care to everyone in their countries at substantially lower cost.

Do you think primary care - and family medicine more specifically - is becoming a more essential part of health care systems around the world?

Definitely. In 2008, the WHO put out a landmark report, Primary Health Care: Now More Than Ever, which described how the way to achieve universal health coverage is to have strong community-based health care. This includes family doctors, but also other members of family practice teams (nurses, midwives, community health workers, allied health professionals, and others depending on the country and context) working together based in the communities where people live. It really got people’s attention all around the world.

What’s something Canada could learn from the region?

One of the great things happening in the region is there’s quite a lot of work to train more family doctors and much of the training occurs in partnership between the countries. For example, a university in Beirut runs a training program in family medicine that is offered to medical graduates from across the region. The specialty examination for the nations of the Gulf States is recognized by all the countries in that area, which allows the sharing of resources and expertise. These are initiatives that people from other parts of the world could learn from.

What surprised you in the book?

One of the things you learn in global health after reading a book like this is that you know less than you think you did because it raises so many new questions.

I found it particularly interesting to read about the delivery of health care services in countries that are in crisis, such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Syria, and in countries like Tunisia and Egypt after the events of the Arab Spring.

For instance, in Syria, where many people have left their homes and migrated elsewhere, and where many of the hospitals and publicly-funded health services centres have closed. This hasn’t stopped, however, many family doctors from still working and providing quality clinical care to members of their communities even though much of the public infrastructure has collapsed.

DFCM is now the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre on Family Medicine and Primary Care: what role do you think our faculty and residents can play in this region?

Our DFCM faculty and residents, along with many other academics across the University of Toronto, already have many strong links to this region, but I think this book opens up potential new opportunities. As the governments in these countries see how they’re performing compared to other countries in the region, they are looking for additional supports, resources, and new partnerships to work together on educating their health care workforce and improving the quality of their primary health care services. These sort of cross-national interactions are great for Canadians as well, because they open up our eyes to what’s happening in other parts of the world, and allow us to gain new insights and share our expertise. Toronto is a multicultural city and many of the countries-of-origin of our citizens are the countries highlighted here, so we have people in this city who already speak the languages and understand the cultures of these countries, which is a wonderful asset. I think anything that allows us all to share knowledge, understanding and experience helps build a better, healthier world.

News